Lines of blue, licks of sugar.

Breaking down & writing about "Blue Raspberry"

I’ve never had much of a sweet tooth. I’ve always leaned tart in my treats. As a kid, I used to bike to the convenience store in West Acton town center to buy Warheads and Sour Patch Kids and that weird hard candy that fizzes in your mouth and makes you crave cold water, like a tiny, thrilling bout with rabies. When it came to sorbet, snow cones, and other frozen summery foods, I usually went for the same piqueish flavor. I was a blue raspberry girl, through-and-through.

What is blue raspberry? It’s a question most often pondered by culinary writers and historians, who have traced its inception back to the late 1950s. It was a time when American consumers and lawmakers were becoming increasingly worried about additives in food, particularly the red dyes that were used to color artificially flavored “strawberry,” “cherry,” and “raspberry” products. According to Bon Appétit, the first mention of “blue raspberry” appears in 1958 in promotional materials for Gold Medal, a Cincinnati company that still sells snack food appliances and street vendor carts. Their electric blue Sno-Kones are made using shaved ice and big ugly plastic vats of syrup. I found the ingredients list online and here’s what goes into the longest-standing blue raspberry product: Water, High Fructose Corn Syrup, Natural and Artificial Blue Raspberry Flavor, Citric Acid, Propylene Glycol, Xanthan Gum, Sodium Benzoate (a preservative), FD&C Blue #1 (E133).

The emphasis there is, of course, all mine. FD&C Blue #1 is also known as “Brilliant Blue FCF.” It’s a synthetic dye commonly used in food, makeup, and medicine. You’ve probably eaten it, since it’s used to dye fruit juices, yogurts, pastries, candies, and even canned, processed peas. It’s also frequently added to drugs, coloring everything from illegal ecstasy tablets to store-bought bottles of Tylenol and prescriptions like Viagra (which, coincidentally, can make you see blue but for a reason completely unrelated to the food coloring embedded in the pill). Have you ever snorted a line of bright blue Adderall? I have, which means I’ve painted the spongy pink veins of my inner nostrils, located right next to the spongy gray matter of my most precious organ, with that shocking, synthetic blue.

The body doesn’t do much with this substance—most of the FD&C Blue #1 we ingest gets pooped back out. It’s generally considered safe, and ironically, this rather toxic-looking color was introduced as a safer alternative to the deep red dyes being used to denote “raspberry” flavors in midcentury American grocery stores. In a world with few genuinely blue foods, I find it funny that we chose to associate this color dye with such a red fruit. At best, you could say raspberries lean purple—more purple than partridgeberries at least, though less so than cranberries, I think—but they’re unmistakably red. Do they taste blue? I don’t think so, but like many people, I’m unable to untangle my “gustatory associations” between blue and sweetness. An article on the “blue steak” myth published in Frontiers in Psychology asks whether blue food is “desirable or disgusting” and posits that it has always been both. Here’s the pertinent bit about blue/red meat:

There is a famous anecdote about an experiment once conducted on a group of unsuspecting diners who were served a meal of steak, chips, and peas under dim illumination. Partway through the meal, the lighting was returned to normal levels of illumination, revealing to the guests that the steak they were eating was, in fact, blue, the chips green, and the peas red. Revolted by the realization, a number of the guests were apparently immediately sick.

After debunking the color-change dinner study (there’s no evidence it actually happened), the authors conclude that there are “crossmodal associations” between color and flavor that alter our appetites. We have cultural associations with various colors (black is for mourning, white is clean, etc.) as well as personal ones and biological ones. While companies have tried to market blue foods as naturally appetite-suppressing, this isn’t effective or scientifically backed. Certain tones of blue may turn you off in the kitchen (like that gray-teal blue of bread mold or the slick vivid blue of bruised veins in raw meat) but other hues are welcome (blue potatoes, blue lobsters, blueberries—even purple-blue steak can be appealing if you know it’s fresh and safe to consume).

Brilliant Blue isn’t always seen in the same saturation, which means it can be several different blues all at once. It’s not as fixed as, say, chartreuse. Whoever decided to pour Brilliant Blue into Curaçao used a heavier hand than the person who wrote the recipe for Jolly Ranchers, but they’re fundamentally the same color. Obviously, you can also use Brilliant Blue as part of a mixture of dyes to color food, which is what I suppose people do to canned peas and smoked salmon. There, the dye is used to color correct, to give people what they want to see from their preserved foods, a pretense of freshness. It’s not quite the same trick, but it reminds me of how food photographers famously use mashed potatoes to stand in for ice cream. It’s a way to make real food appear even more food-like, something we need in this age of toxic semblance and excessive substitutions.

Even knowing the name of a food dye feels like seeing behind the curtain, a little sausage-making reveal for your candy crush. I don’t want to stoke fear, but many countries do ban the use of Brilliant Blue, which seems like a bad sign. It’s probably not good for you to ingest it, and in large enough quantities, it can be lethal (of course, so can water). Yet my familiarity with blue raspberry hasn’t bred contempt or distrust. It’s an uncanny, unnatural blue, a too-blue blue, but I don’t hate it. I like it; I distrust it.

I’ve always worn a lot of it, for my eyes are blue-toned and I think it looks decent with my pale cheeks. I remember once trying on a dress in Anthropologie, walking out of the little dressing room, and hearing the shopgirl gasp. I was 23, it was my birthday, and I was highly susceptible to suggestions disguised as compliments. “That color is amazing on you,” she cooed. It was a button-up shirt dress, rayon, electric blue with a faux-ikat pattern of white splotches, and a wide sash belt. “You must be a summer,” she said, and I remember nodding in agreement, though I didn’t know what she meant. Despite being an avid reader of color analysis subreddits and a frequent taker of online tests, I still don’t.

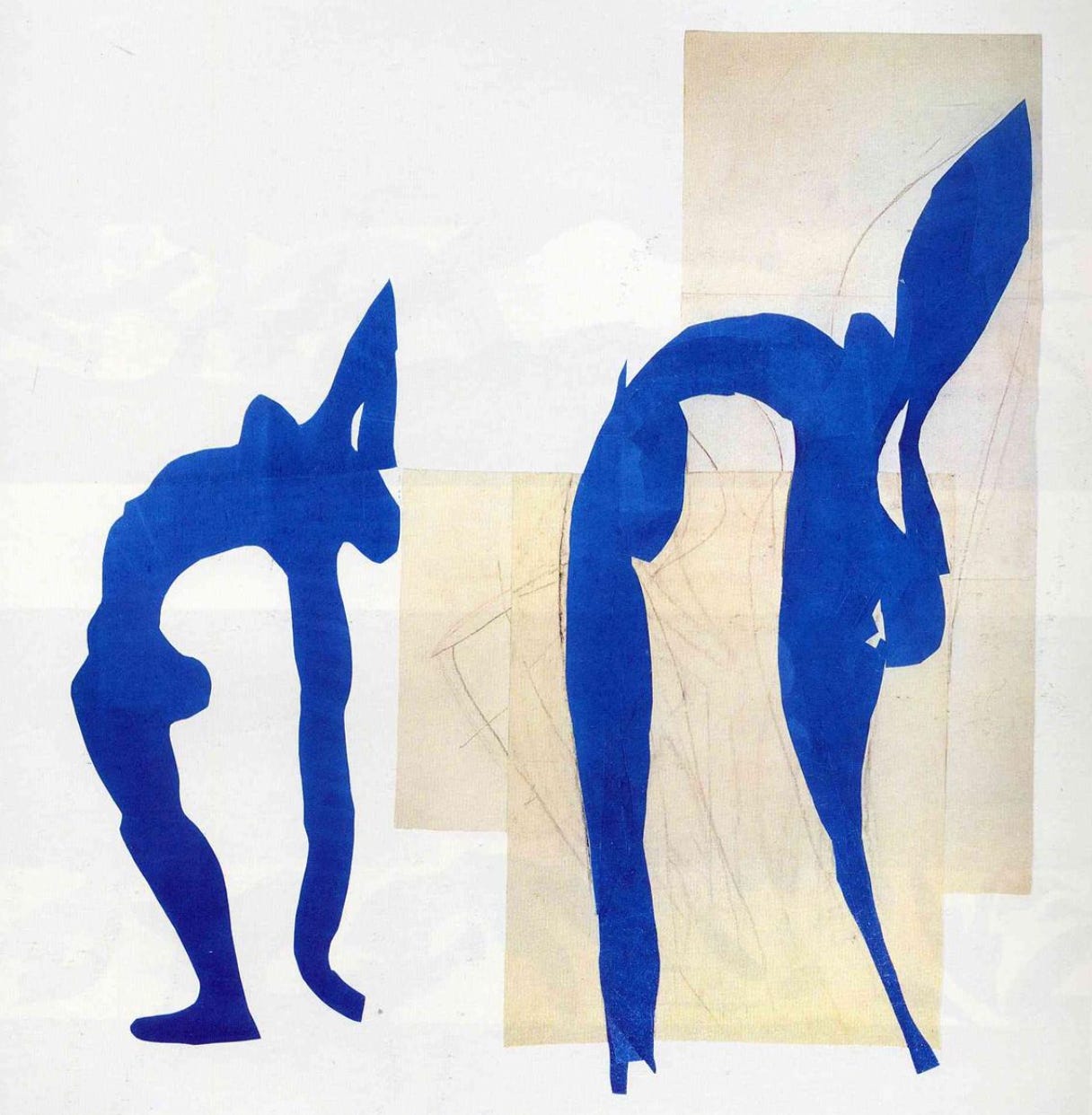

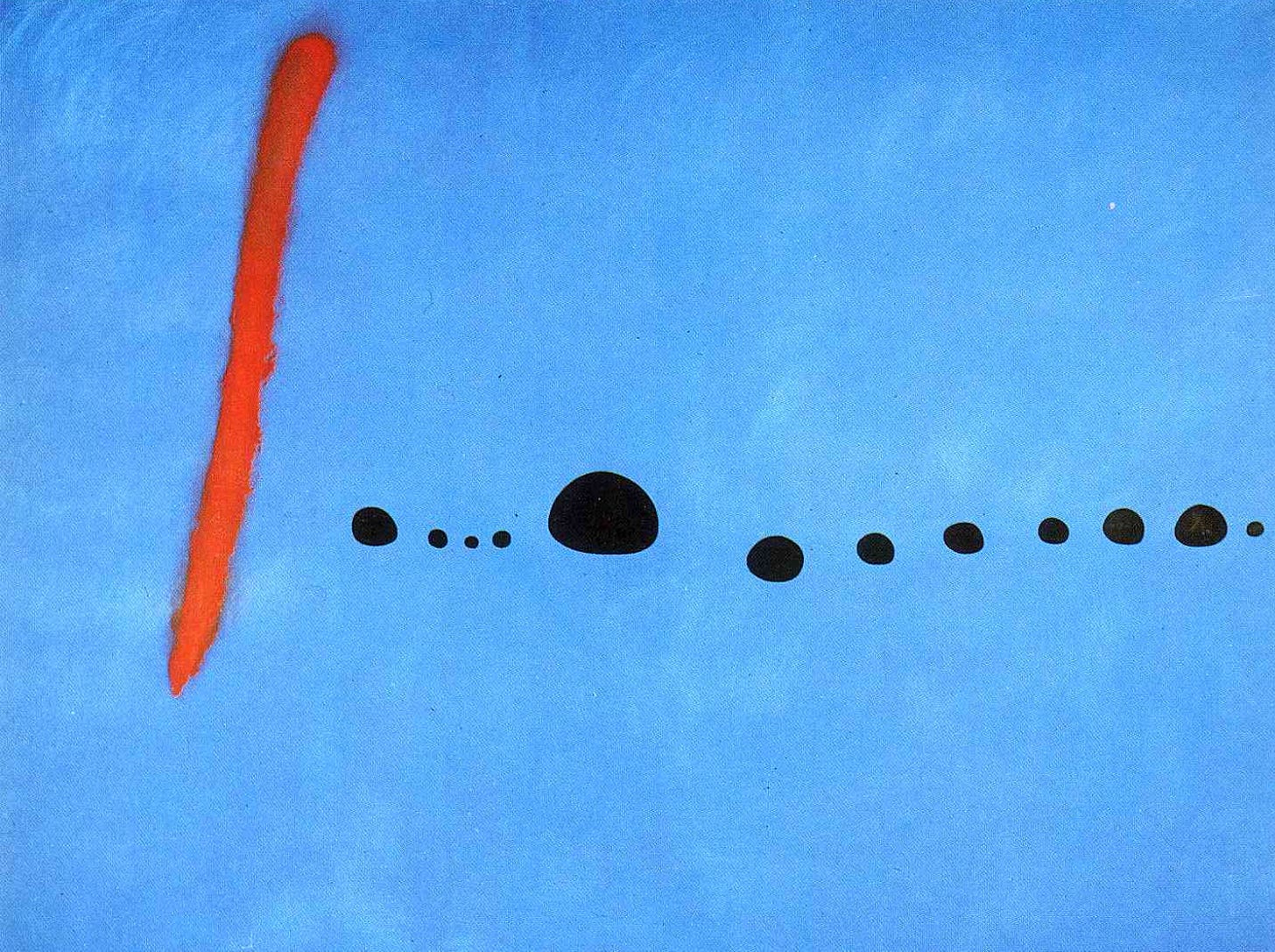

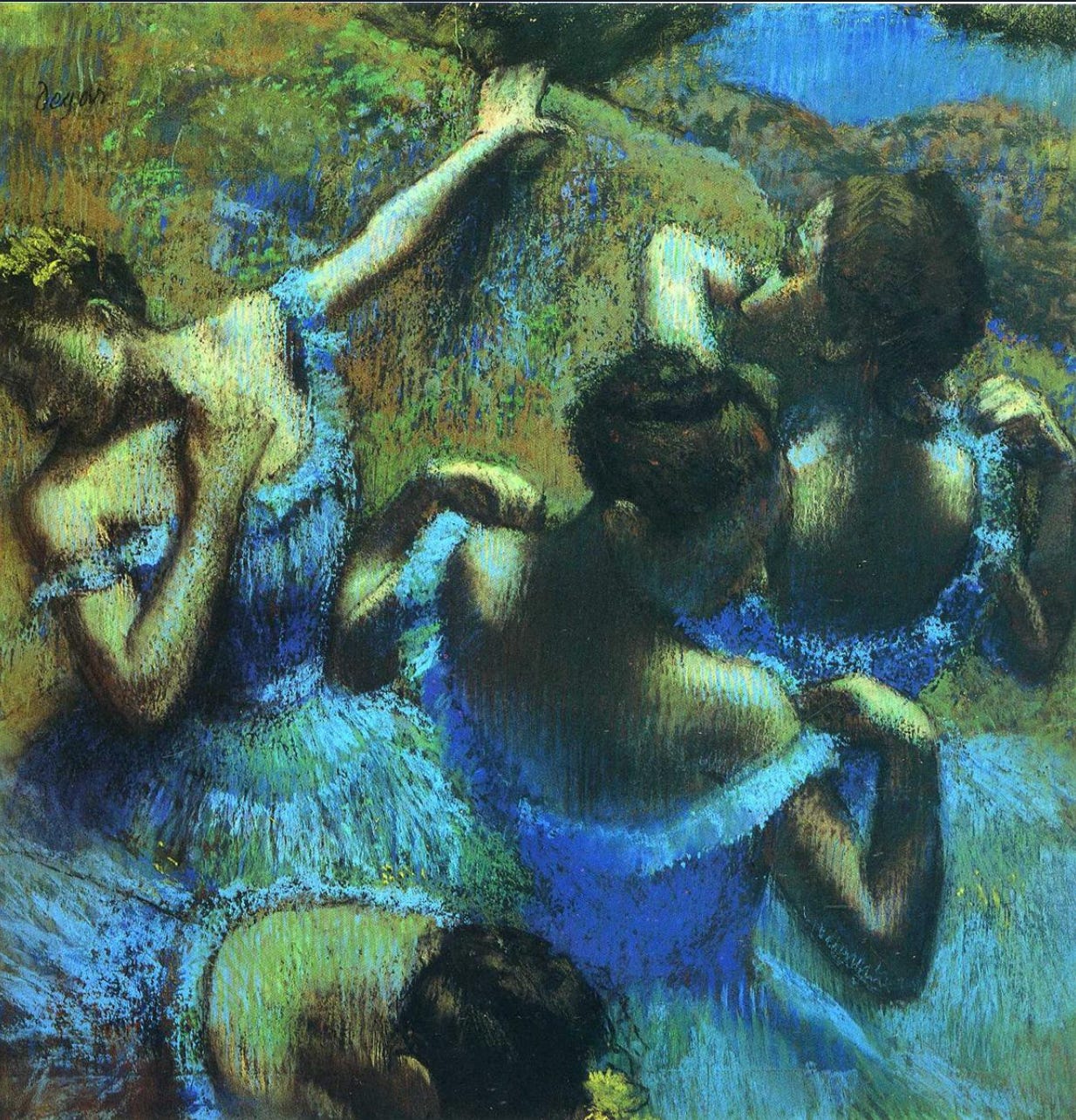

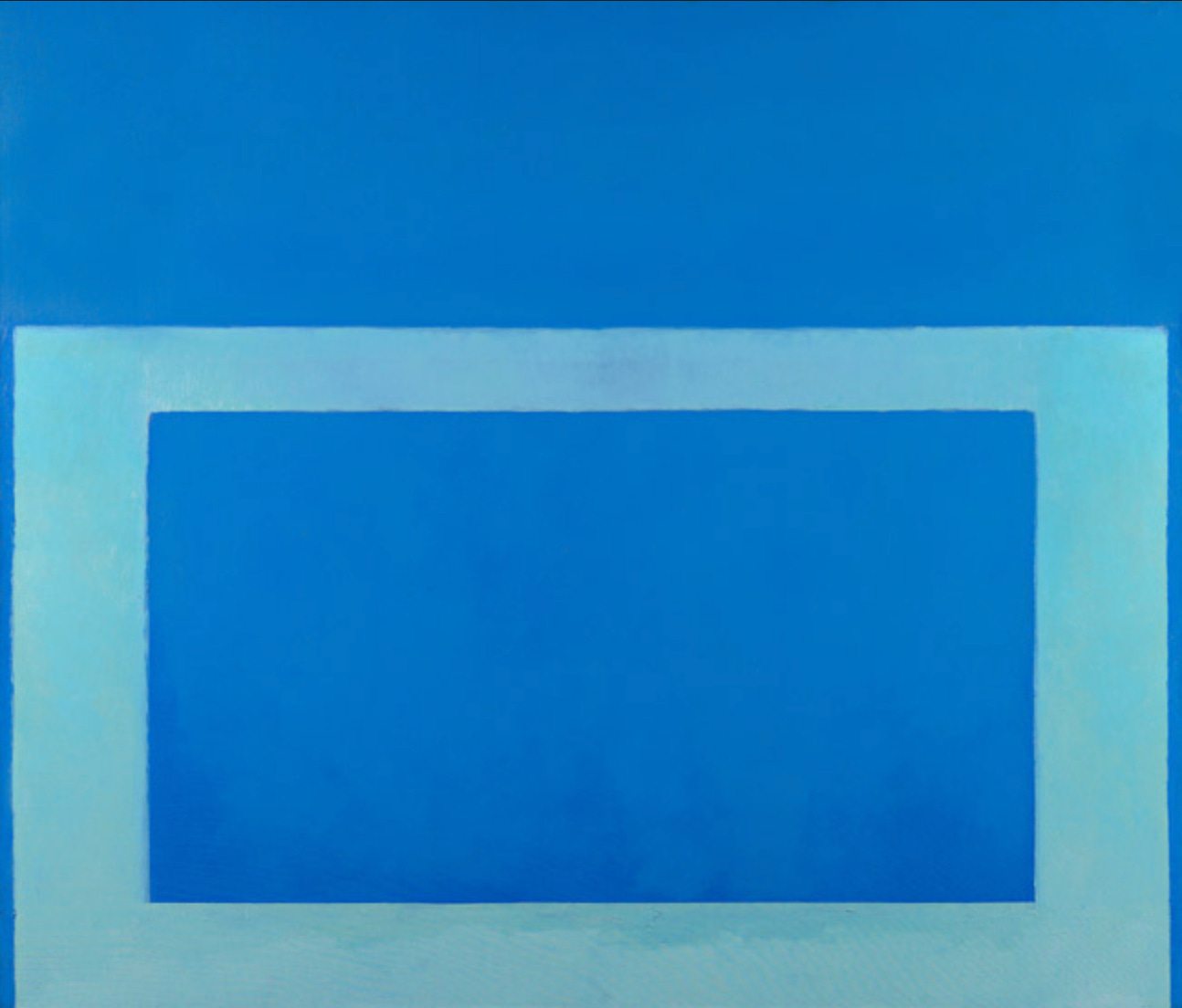

When it comes to my closet, I continue to favor the bold blues, big loud hues that get names like Wes Anderson anti-heroes (Royal, Brilliant, Cobalt, Smalt). But while I like how they look on my body, I don’t really like the associations I have with these hyper-real colors. Unlike the baby blues or the indigos of the world, this is the kind of color that becomes an artists’ trademark, like Yves Klein blue or Matisse blue. The fact that it’s rarely found in nature, well, that’s the point. This is a human blue—a mankind blue. It’s a bright, saturated, pure color, but it reads as masculine, which is unusual in American culture. It’s also a techy blue, a digital hue. Looking at my computer screen, it’s the color of the Safari logo, the Zoom logo, the Microsoft Word logo—all of which I have open right now. Although the World Wide Web has changed colors over the decades, when I came of age, it was very blue, and I don’t know if I’ll ever break the mental link between blue light and glass screens.

Blue raspberry is a nostalgic color, one that makes me slightly ill now. It’s not the sweetness that invokes such a response, but the link between that color and my 90s youth. That was a time when I still believed many of the overly hopeful myths about American progress that had been passed down to me from my parents’ generation. There was a time when I thought America was the greatest country in the world. There was also a time when I thought we were the most terrible. During that loud period (Bush-era), I tended to look at my elders and scoff, discarding them as a dangerous, wrong-headed, selfish cohort that needed to move aside, let someone else lead. In my early 20s, I found my parents certainty and complacency disgusting.

But Boomers didn’t blow up the world. Many of my elders fought for equality and freedom. I’ve met dozens of lovely, idealistic, generous Baby Boomers, people who held onto the sweet hippy dreams of better lives for all, greater equality, and America as a melting pot. But they’re outnumbered by their loudmouth siblings. Ironically, the groups that are most opposed to classic American values tend to be white and lean red, though of course there is plenty of bitterness and anger embedded deeply within the democratic party, too. A blue voter isn’t automatically good (nor is a blue check, but I digress).

I’m sorry. I didn’t start this piece with the intention to write about politics. That’s not what you came here for! But the more I think about Brilliant Blue, the more I realize: this color is tricky. It’s the color of assumed progress, assumed safety, assumed innocence. Sweet, fake, intense, showy. It’s not the worst choice in the world, but I can name a dozen better flavors.