Heliotrope for daze

The color of fictional cults, dog-killing flowers, and half-mourning Victorians.

Thanks to Yellowjackets, I have heliotrope on the brain. For anyone unaware, Yellowjackets is a TV show about a girls soccer team that gets stranded in the Canadian wilderness on their way to play a Big Game (nationals in Seattle, I think). The show is set in 1996, when the plane went down, and in 2020, when the girls with issues have grown into women (with even bigger issues). It’s funny and weird, and it deals with themes like trauma, grief, sex, violence, and above all, the power of belief. There’s cannibalism and cults and sacrifices to the wilderness and all sorts of good stuff. There’s also a group of present-day weirdos who live in an “intentional community” and wear only one color: all their clothes are dyed with heliotrope.

I think the writers of the show decided on the color because it’s a little obscure (but not too obscure), derived from a toxic plant, and because it’s a shade of brilliant, shocking purple (perfect for people-eaters). According to an interview with costume designer Amy Parris, heliotrope appealed because it’s “gender neutral” (debatable) and “welcoming” (also debatable). “They want to visually see that this is an inviting space for all,” Parris told Fashionista when discussing the lilac-draped yogis. She also reveals that the community and their costuming was inspired by “Wild Wild Country” on Netflix, a documentary about the Rajneeshpuram community in Oregon. In this IRL place, all the members wore head-to-toe maroon—the color of the sunrise. (Another supposed reference point was Teal Swan, a dangerous guru named for a hue, one that she wears often and well.)

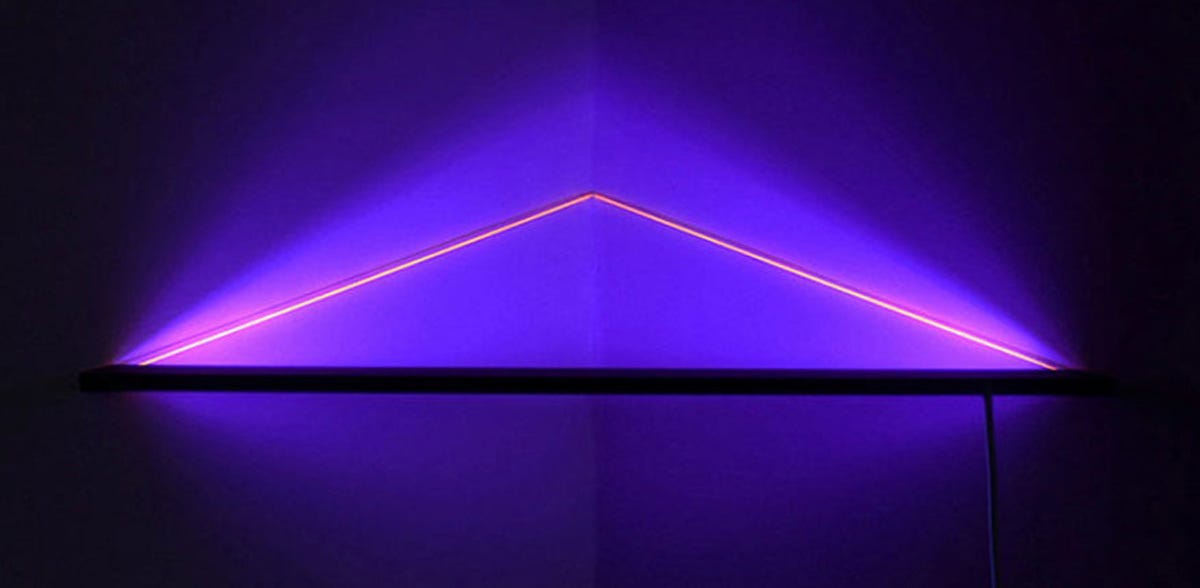

To me, there’s nothing soothing about heliotrope. I think there’s an undercurrent of eeriness in this color. It comes from the unnaturalness of it, for although the color is named after the vivid clusters of blooms that form on some members of the Heliotropium genus, it doesn’t feel like a safe, familiar purple. It doesn’t have the dark, vegetal draw of eggplant, it lacks the shiny, rosy hue of plum, it isn’t soothing and neutral like periwinkle nor is it moody and distant like indigo. It has an electric feel to it, jarring and jolting, like Barbie pink or highlighter yellow. It’s close to magenta, but features a little more blue. When you search for it online, the color that comes up is closest to ultraviolet, that impossible color named for rays of invisible light.

Heliotrope isn’t fluorescent, necessarily, but it can be. It can be luminescent. It can also be flat and matte, captured and imprisoned in a piece of hand-dyed cloth. It is not uniquely related to light—all colors are born of light, and all light is composed of color—but it’s name seems to suggest a stronger link than just… purple. Heliotrope, the plant, has a notably sun-ward bent. Like petunias and morning glories, these flowers orient themselves towards the light source, towards Helios in his golden chariot. And like carnations and narcissus, these flowers have a dark myth attached to their soft blossoms.

Let’s take a break for story time: There was once a water nymph named Clytie who had an affair with Helios, the handsome playboy sun god. Clytie loved Helios very much, and very faithfully. And though she was fair of face with salt-bleached hair, a touch of gold herself, she couldn’t hold Helios. Their dalliance didn’t last long; his head was soon turned by another pretty face. Clytie lashed out at her rival and arranged to have the girl buried alive with only her head exposed (truly, a horror). But still, Helios didn’t return to Clytie. It wasn’t because he was angry at her brutality—violence is a language the gods speak glibly—he’d simply lost interest. Clytie couldn’t cope. Instead of moving on and finding a nice merman or lesser god to settle down with, she stripped bare and planted her ass on a cliff. For nine days, she watched her former lover blaze across the sky. For nine days, she refused food and wine. For nine days, she waited. He never came back.

The sad, jealous, loving, savage girl became a flower—a heliotrope. A sun-turner, a light-watcher. But in telling this myth, the ancient Greeks weren’t referring to the brilliant purple plant we know today. (It’s native to North America and unlikely to have been growing on a rocky cliff in Greece.) She must have become some other heliotrope, perhaps a lighter lilac or a white bloom, or maybe even a different flower entirely. Some say Clytie became a sunflower, though that’s equally improbable. Maybe she became a mythological flower, one with no real world equivalence. Maybe the storytellers weren’t really concerned with the flower, maybe the point was she turned violet and small, shriveled little and starved, weak and aching, yet still willing to watch.

Was he worth it? Of course not, but devotion makes for a good story. Reading about Clytie, I couldn’t stop thinking about another bit of pop culture I once loved. (Stop reading now if you care about spoilers for a 20-year-old movie.) In 2002’s Secretary, Maggie Gyllenhaal plays a lovesick office worker, obsessed with her boss, played by a golden-haired, sullen-yet-sexy James Spader. She’s a masochist, he’s a dominant deviant. But he becomes bored, or afraid, or maybe just tired of the games. He drops her but she refuses to be dropped. She dons a wedding dress and sits in the office chair, pissing herself for ten days straight, crying, waiting, pining for love.

At the end, Spader spanks her purple again, her bruises (we’re supposed to believe) a form of love. Maybe they are.

I’ve never seen a heliotrope-colored bruise but this probably has to do with my good fortune. I bruise easily, “like a peach,” but I’ve never been beaten. (Not like Lottie was on Yellowjackets, that’s for sure.) I know bodies can turn all kinds of colors. Skin-toned was always a bullshit descriptor, even before the white world of makeup remembered that brown people exist.

Now, there’s one last thing I wanted to add about heliotrope, and it has to do with the Victorians. (Doesn’t it always? What a long shadow they’ve cast over culture.) As you probably know, there were strict rules that governed mourning for nobles in 1800s England. You couldn’t just be sad and call it a day. You had to perform your sadness for the public for two years. Toward the end of your prescribed grief, you were allowed a slight reprieve from all that drab, washed, faded black cloth. You got to wear purple. Heliotrope or lilac. As always, flowers for the dead.

During the years I’ve been researching color, I’ve greatly expanded my vocabulary. But I have to admit: I’m not going to start calling things “heliotrope.” It’s too stuffy, too Victorian for daily use. Plus, the actual purple reminds me of happier plants: candy phlox, rhododendrons, hanging fuchsias. I’m going to leave Clytie on her cliff edge and Maggie at her desk and forget about those sad girls with their bruised hearts.

obsessed

Awesome