Last winter, I went swimming in the Pacific Ocean. We were in San Diego to visit my brother-in-law, and it was late December, so the water was cold. It wasn’t the right time of year for water to be a relief but it wasn’t a punishment, either. I think the right word for the Pacific is bracing. It stimulates the nerves, it enlivens your body. You have to brace yourself against the waves, so much more powerful than the ones we got in Maine, and, if you happen to be surfing or trying to swim past the break, you have to be wary. You have to calibrate the motions of your entire body towards the swell and drag of the water, switching your vision constantly from horizon to middle-distance, watchful. Braced.

It was lovely to try and surf in the Pacific—difficult, invigorating, joyful. There were dolphins. I didn’t know that was something that actually happened: on an ordinary weekday, one could swim next to slick, dark mammals. By all rights, I should have fallen in love with the Pacific then, drawn into its bounty as I was. But I remain a worshiper of the Atlantic, my original ocean.

Aside from the obvious reason—I best love the ocean that I know most intimately—there’s the problem of color. The coasts of North America show different sides of that same body of water. On the west coast, you have blue. On the east, you have green.

Well, not just green. The water off the coast of Maine isn’t green-green, though you do sometimes see an almost bottle green crash of seaweed in the shallower waters by the peninsulas. It’s not turquoise—it’s a wilder hue than that. It changes constantly with the weather and the shifting light, but when you get a chance to watch a wave break from a head-on perspective, you get to see its best color. It’s a semi-translucent teal, similar to duck green, like a blue spruce bough in winter. It’s a neither-here-nor-there color. It’s my favorite.

It’s fairly well-known that the east coast has green water and the west coast has blue, and the explanation for why this happens is simple enough. The Atlantic has more phytoplankton living in its waters, thus sunlight can’t penetrate as far into its depths, and you get that greenish color. When light can penetrate into the deep recesses of a body of water, it tends to appear a darker blue, because that wavelength goes further. “Scientists have worked out ht exact colour that can travel furthest through water without being absorbed: it is a blue-green colour,” writes Tristan Gooley in How to Read Water. “They have even worked out its wavelength: 480 nanometers.”

What color is 480 nanometers? “A typical human eye will respond to wavelengths from about 380 to about 750 nanometers,” explains Wikipedia. Red rings in at 625-750 and violet comes in at 380-450. 480 is somewhere in the blue region, a shorter wavelength (red is the longest). Of course, what we see when we look at the ocean depends not only on what’s in the water, but also where we are standing. If you’re standing on shore, you’re not looking down into the water, but out at the surface. The color of the Atlantic, viewed from a distance, is determined by the color of the sky. Sometimes, it’s steely, matte gray. Sometimes, it’s a glimmering pale blue. But when you know it intimately, when you are swimming within it or standing on a ferry, looking down at the churning below, then you get the true color. You get teal.

This may seem unimportant or obvious—of course the sea is teal! Of course clean water is blue! We’ve all been to a swimming pool, after all. Or at least, we’ve all gotten into a pristine white bathtub and looked down to see the slightest blue tinge. We know what color water is—it’s not really colorful or exciting. Yet it matters quite a bit to sailors. “The difference between the colour of the sea in deep water and shallow water has led to a common nautical expression, ‘blue water sailing,’” points out Gooley. “‘Brown water’ is not used quite so much now, but it refers to a shallower water, the convention being that blue water is the sea up to 100 fathoms deep and blue water is anything over that.” Early sailors used every tool in their navigational toolbox to help them avoid rocks, reefs, and other dangers. Not only did they analyze the wave patterns to know where islands could be located (Polynesian boatmen weren’t just striking out blind when they populated the South Pacific) but they also used their knowledge of water’s many hues to get around safely. This is, Gooley writes, “a very practical art,” even now. “GPS together with the latest electronic charts still fail to beat a knowledgeable local skipper whose eyes are tuned to the faintest lightening of the blue water. Even an electronic depth gauge, like an echo-sounder, is pathetic compared to these color changes since it can typically only measure depth beneath the boat, not tell you how that changes all around you.”

Ocean color also matters to scientists, who have been tracking the color of the ocean for the past couple decades. Using images captured by NASA satellites, researchers have been able to document notable changes on the surface of the water, changes that reflect shifts happening far below. “The differences in color that the satellite picks up are too subtle for human eyes to differentiate,” writes Jennifer Chu for MIT News. “Much of the ocean appears blue to our eye, whereas the true color may contain a mix of subtler wavelengths, from blue to green and even red.” The most drastic changes are happening near the equator. Here’s more from MIT News:

“I’ve been running simulations that have been telling me for years that these changes in ocean color are going to happen,” says study co-author Stephanie Dutkiewicz, senior research scientist in MIT’s Department of Earth, Atmospheric and Planetary Sciences and the Center for Global Change Science. “To actually see it happening for real is not surprising, but frightening. And these changes are consistent with man-induced changes to our climate… The color of the oceans has changed. And we can’t say how. But we can say that changes in color reflect changes in plankton communities, that will impact everything that feeds on plankton. It will also change how much the ocean will take up carbon, because different types of plankton have different abilities to do that. So, we hope people take this seriously. It’s not only models that are predicting these changes will happen. We can now see it happening, and the ocean is changing.”

This means that the Atlantic, my ocean, my personal watery haven, may change color at some point. Currently, it’s teal, but someday it might veer more turquoise, like the Carribean, or true blue, like the Pacific. I am not a climate expert, so I can’t really say what will happen (generally, I don’t trust people who tell me what the future holds—only what may come to pass) but I imagine I’ll be pretty sad if one day, 50 years from now, I’m left with only my memories of the cold teal waters of my youth. Although solastalgia is, for now, a term primarily used by writers and philosophers, I have a feeling that we’ll all be experiencing this particular grief as the anthropocene rolls onwards. The changes that are visible from space, using special tools, will become observable differences, ones that affect every aspect of our lives, including our aesthetics. Someday, an en plein air painter will set up her easel on Prouts Neck and get to work, and the image on her canvas will look nothing like Homer’s wild seascapes. It may be still beautiful, but it probably won’t be the same.

As usual, Katy, I could rhapsodize about each paragraph in your stories, but I'll not be so self-indulgent. Besides, I can't think of any writer who wants to receive compliment after compliment-- I mean, how tedious, right? : )

I'll say this, though. One of my all-time, all-time favorite writerly quotes comes from Mark Twain: "A powerful agent is the right word." And one of the reasons I enjoy your writing so much (and recommend you to fellow wordsmiths) is that your words are so precise and delicious.

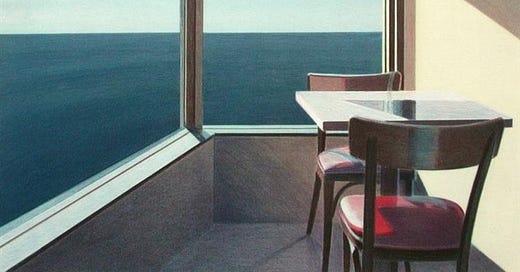

Though you didn't reference the paintings as overtly in this piece, they're nonetheless brilliant choices. I didn't want to let that escape notice. I'm a Pacific Ocean guy myself, and coincidentally found myself flying over it last night (window seat no less). Our family took a trip to Carmel-by-the-Sea in the 1970s or 80s (I just know I was a kid), and my Dad brought back a seascape by Alexander Dzigurski (who I moments ago learned has been called "The Poet of the Sea"). When we'd have guests over, Dad loved to play with the dimmer and show off the painting-- it really was something! In dim light, the crashing waves were wintry and forbidding, but as the spotlight increased, it seemed to come from behind the waves, a shimmery aquamarine. Dzigurski returned to the same subject matter repeatedly, so "January Storm" looks like any of these: https://www.dzigurskigallery.com/alexander-dzigurski-i/seascapes

Something else you wrote stands out: talking about our tendency to see a single shade of ocean blue, where many subtler shades exist. This makes me think of one of my favorite notions, that we perceive the moon to be chalk white or gray, but in reality its minerals are beautifully shaded. There's a zillion versions of this online, but a trustworthy example can be found here. It's nice because you can manually adjust the saturation and watch the colors emerge: https://telescopius.com/pictures/view/134645#saturation=0.51

Fascinating as always!

What a useful, poignant word solastalgia is. Thank you for the introduction as this word and I will probably become quite good friends.