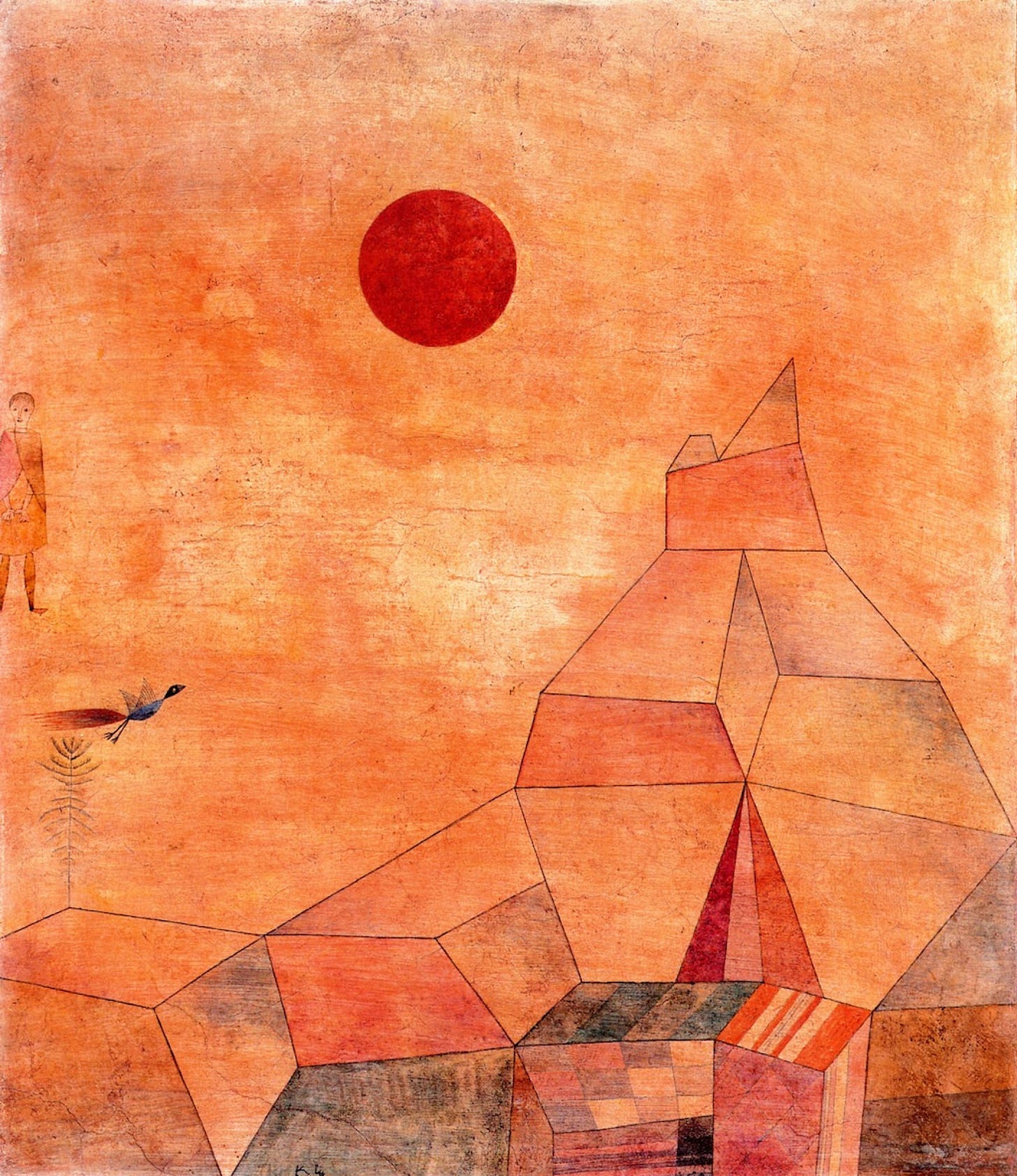

Paul Klee was not a born colorist. For him, making sense of color was a struggle. Line and shape he seemed to grasp intuitively; even his earliest works show a certain playful understanding of form and motion. But color? Color didn’t come to him until he became a bit more worldly. According to the artist’s own diary, Klee became one with color in Tunisia. “It penetrates so deeply and so gently into me, I feel it gives me confidence in myself without effort,” he wrote. “Colour possesses me. I don’t have to pursue it. It will possess me always, I know it. That is the meaning of this happy hour: Colour and I are one. I am a painter.”

Before his breakthrough, Klee had tried—and failed—to become an illustrator. He had training as an artist, but he primarily served as a homemaker. His wife, Lily, made the family’s income teaching piano lessons in Munich. She was quite talented, but so was he. I think he just needed something extra, a jolt of inspiration, a hit of warm African light. He needed to find his orange.

Over the next several decades, Klee mastered color to the point where he was able to eloquently teach and write on the topic. He knew his Newton inside and out. So perhaps it’s just me, but when I think Klee, I don’t think of blue and gray and red. I don’t see a rainbow; I only see apricot.

Well, apricot and salmon and coral and tangerine. Maybe some green, and yes, a bit of mustardy yellow. But my favorite of his works all exhibit that same earthly orange glow, that burnished, dry heat, which elevated his childlike linework and rough geometry into something transcendental. Apricot made his moon faces appear godly. It gave his whimsical figures an odd sophistication. It brightened his darkness, mellowed his sharp edges, sharpened his dull corners. Klee was a painter who eschewed symmetry; orange was a color that answered that call.

Like all shades of orange, apricot came late to the English language. For a long time, orange was described rather than named, “yellow-red” or in the case of Chaucer, “betwixe yellow and reed.” In the 16th century, the term was “tawny”. The use of “orange” only became widespread during the 17th century, after Portuguese traders began bringing the citrus fruit from India to Europe. The first recorded usage of “apricot” as a color-name happened in the 1850s, according to Wikipedia. I think most of us are familiar with the Crayola version, which is light enough to feel more like a pastel than a secondary color. (Unsurprisingly, the crayon made its debut in 1958. Aside from the 2010s, I can’t really imagine a decade more enamored with peaches and pinks than the 1950s.)

“Along with the heady smell of green chile roasting in the fall and the beauty of crabapple blossoms decking the city in mid spring, the sight and flavor of fresh ripe summer apricots is one of the iconic sensual delights in our city of enchantment.”

- Linda Churchill, Director of Horticulture at the Santa Fe Botanical Garden.

In my neighborhood, the apricot trees make too much fruit. Personally, I love it, but I’ve heard other adults complain about how the orange orbs fall heavily on the sidewalks and bring the bees. They rot, they fester, they turn into sticky leather underfoot. Yet they also fill the air with perfume, a light and bright smell, and they fill my daughters’ cheeks with fruit. For there is so much bounty, so many apricots, I tell her to pick them quickly and enjoy, not to worry about stealing. When the boughs hang over adobe walls, the fruit, I’ve heard, is considered free.

Apricots thrive in the southwest, but they most likely originated in Afghanistan. I think quite often about how many of my favorite fruits come from this region of the world, and how many of them are related. Apricots, like apples, plums, cherries, strawberries, and almonds, are members of the Rosaceae family, which is, of course, also home to roses. All members of this family have five-petaled “showy” flowers. (The flowers come in a variety of colors, from orange to pale pink, but none of them are ever blue, a fact that is important if you’ve been paying any attention at all to the quest for a blue rose.) Apricots belong to the Prunus genus, and they’re technically a “drupe” or a stone fruit, though I happen to adore the word drupe. It’s so ugly and funny! Drupe.

But anyway, apricots are ancient fruits; humans have been cultivating them for over 5,000 years. It’s gone by a number of different names over the centuries, according to Joel Denker, author of The Carrot Purple And Other Curious Stories Of The Food We Eat. Translated into poetic Arabic, amardine means ‘moon of the faith,’” he writes. “The Romans, who learned of the apricot in the first century A.D., dubbed it praecocum, the ‘precocious one.’ They noticed that the fruit bloomed early in the summer.” Chinese merchants called the fragile fruits “yellow plums,” and it’s one of several candidates for the mythological “golden apple” that appears multiple times in Greek stories and Irish legend. (In the most famous tale, a persistent suitor uses golden apples to distract the huntress Atalanta during a footrace, thus winning her hand—though probably not her heart.) It seems that most folklorists agree that the “golden apple” was probably an orange, but I prefer to think it was an apricot. Not that it matters; myths are full of golden things that are, I suspect, simply golden versions of other items. Gold because they’re holy, gold because they’re great, gold because that is precious and godly and because no other material speaks so clearly of the sun.

But I digress, again. For me, the most important golden apple is the one from the Yeats poem, “The Song of Wandering Aengus”. I first read this in high school, and it remains one of my favorite poems of all time, and one of the few I can recite from memory. (Not to brag, but I also have a Hardy and a Frost or two, plus the better part of an Oliver. I sometimes use them to stave off panic attacks.) In case you’re not familiar, the three short, rhyming verses tell the story of a man who went fishing, caught a trout, turned his back to light a fire, and then turned back around to see the fish had transformed into a girl. Like Atalanta, she runs from him, unwilling to be caught and caged. It’s unclear whether the narrator’s desire is for matrimony, or just to see the fish-girl again, but either way he spends the rest of his life searching for her. Here’s how it ends:

Though I am old with wandering

Through hollow lands and hilly lands,

I will find out where she has gone,

And kiss her lips and take her hands;

And walk among long dappled grass,

And pluck till time and times are done,

The silver apples of the moon,

The golden apples of the sun.

Beautiful, no? The yearning, the longing, the imagery of hilly lands and long dappled grass and an infinity of footsteps. Certainly, he could be speaking of an orange, but I think he was dreaming of precocious, sensitive, early-blooming fruits with tawny velvet skins and luscious orange flesh.

Are you a convert to orange yet? Apricot does it for me, I’ll freely admit.

So if you, too, have become a little apricot-crazed, I have a few suggestions. First, get your hands on some Amardine, aka dried apricot paste. It’s imported from Damascus and it comes in these thick orange sheets that are chewy, tangy, and a little musky but in a great way. Next, perfume yourself with apricot-forward perfumes. I asked my friend Rachel Syme, who is a genius when it comes to these things, if she had any recommendations. “I do!! Sadly it’s a GOOP Perfume called Orchard number four that has been discontinued, but I’m looking around to see if I can see where you can get a bottle,” she generously wrote, before going on to suggest this and this, both of which I’ll be testing ASAP. If you love the color, but not the fruit, maybe try searching out some Oregon sunstone. This is on my bucket list now; aside from berry picking, nothing gives me such primal, hunter-gatherer joy as rock collecting.

I wanted to take a minute to say thank you to my paid subscribers. I don’t paywall content because I care deeply about making my work accessible. I believe everyone should be able to access sources of beauty and inspiration, and I want to live by that. But, since we live in a world that requires money for groceries (and more of it, every day, it seems), I do deeply and profoundly appreciate the people who choose to support my work. Thank you. I know each one of your names, and your generosity hasn’t gone unnoticed.

With love,

Katy

I'm a fan of your eloquently subjective takes on color. I wish I could concur about apricot as a color, or even as a fruit, although I can understand the viral trend of Aperol spritzers. But apricot, to me, is an unfinished orange as a color, a tad too pale. I go for the orange in Pontormo's The Visitation https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Pontormo#/media/File:Pontormo-visitation-after-restorationRGB.jpg. It shocked me at first, wondering how ahead of its time it was in the billowing shamelessness of its challenge to the blue, pink and pale green the other women are wearing. I love to see a bright orange, even in paintings I don't like so much, like Frederic Leighton's Flaming June. But with Klee, it's a rollercoaster of shades that make his paintings endllessly fascinating. I even accept an apricot peeking out here and there, now and then.

“He needed to find his orange.”

Wonderfully written line that has so much further context.

Great piece.

Thank you.