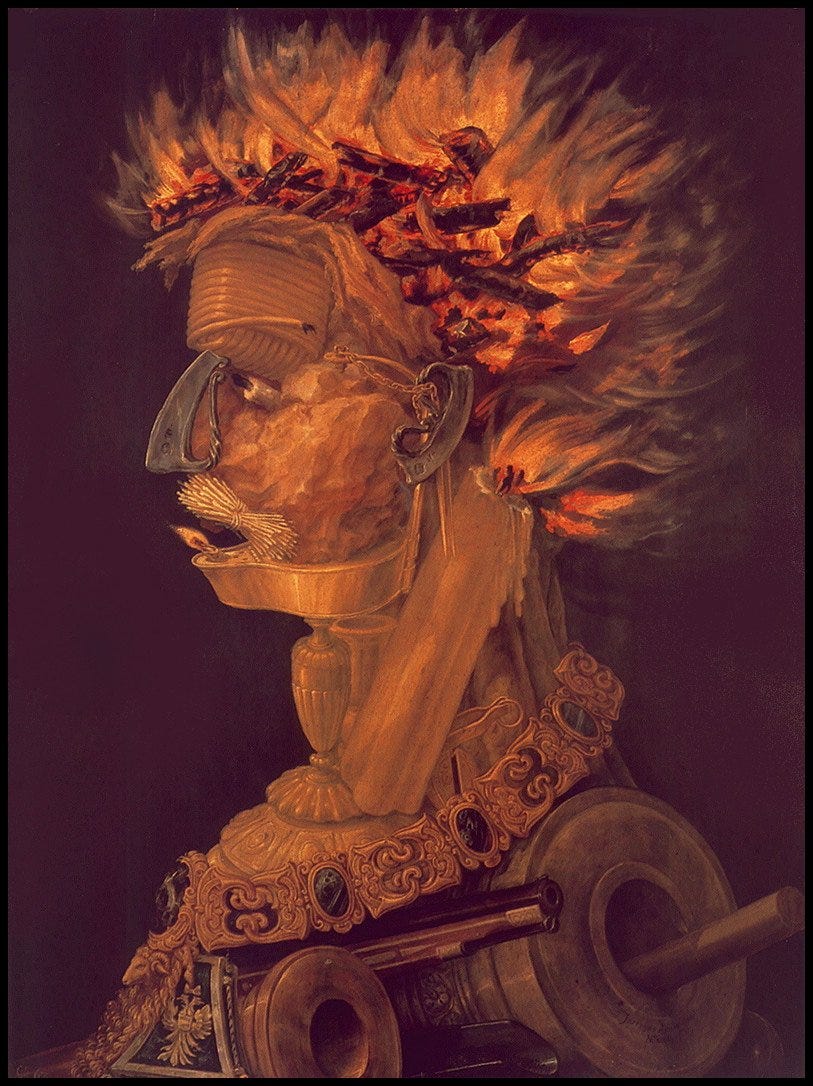

Of all the elements, fire is the one I understand the least. Water is the universal solvent. It’s what runs through our veins, it’s the ocean, it’s life. Earth is soil, potting and otherwise. It’s full of bacteria and fragrance and built of so many tiny minerals and dead things, but it’s alive in its own brown way. Air, too, is rich with the thingness of the world. Even when it’s not misty and damp, it still carries objects in its amorphous mass. You can fly through the clouds or watch them from below, and you know they have a sense to them, a weight. Fire though? It’s combustion. It’s a chemical reaction. It is a process; it takes matter and changes it. All the other elements I can understand on a physical level, as objects that exist and mean something to me and my survival. Fire is different. The thingness of fire is found only in its residue. Fire is not in the log. Fire is in the coals, the soot, the smoke, the ash.

There is no one color of fire; it can be all colors, depending on what it is acting upon, what is being combusted. But there is a color that comes from fire, born of it. It might be our oldest color, the first one we made. It’s lamp black.

To make lamp black, all you need is an oily substance, a piece of metal, and a bit of liquid. You light the oil, interrupt the flame, and collect the soot on the metal. Then, you can scrape off that fine, dark substance and mix it with a liquid. The resulting ink can be used to tattoo your best friend or practice your calligraphy. It can be made into paint or a glaze for ceramics. It’s an incredibly versatile substance, and we still use it often. These days, you might see it listed as “carbon black”, though really, it’s all the same sooty stuff.

That’s my modern bias talking, according to historian Michel Pastoureau, who not only wrote books on blue, green, red, and yellow, but also a great tome on black (Black: The History of a Color). After discussing several of the ways that ancient people made black—by burning bones, wood, vines, fat, etc.—he argues for the sophistication of our ancestors. “Ancient cultures had a more developed and nuanced awareness of the color black than contemporary societies do,” he writes. “In all domains, there was not one black, but many blacks. The struggle against darkness, the fear of night, and the quest for light gradually led prehistoric and then ancient people to distinguish degrees and qualities of dark, and having done so, to construct for themselves a relatively wide range of blacks.” Ivory black was the most prized but since it required burning expensive bones, it wasn’t as common as plant-based carbon blacks. By the time the Greeks came around, Pastoureau argues, artists, writers, and dyers had developed a wide range of dark pigments. They were able to make glossy black tile floors and bluish-black wool cloaks. Fittingly, there were also multiple words for black that emphasized and distinguished the texture rather than the hue. (Think luminous blacks versus matte blacks versus grainy blacks versus silky blacks.) Latin, too, had more than one word for black. There was niger (shiny) and ater (flat).

Carbon blacks tend towards matte, especially in their raw form, which makes them more ater than niger. This seems fitting; over the years, ater took on other meanings than simply “black, but flat.” It became a term for all things dingy, dirty, despicable, dull, malevolent, and atrocious. I couldn’t find any linguistic connection but reading that tidbit about ater reminded me of the figure of Ate. She was, according to some sources, a favored daughter of Zeus, though other sources called her the child of Eris. She was the personified spirit (daimona) of “delusion, infatuation, blind folly, rash action, and reckless impulse who led men down the path of ruin.” Writers used Ate as a scapegoat for men’s failures. She had a tendency to darken and obscure their vision—she could even fool Zeus. “Her feet are delicate and they step not on the firm earth, but she walks the air above men's heads and leads them astray. She has entangled others before me. Yes, for once Zeus even was deluded, though men say he is the highest one of gods and mortals,” wrote Homer. But though Ate may have been atrocious, she was also bright and shining, light of hair and step. So I don’t know what to make of it, of her, of the words for dark and light, except this: they’re tricky.

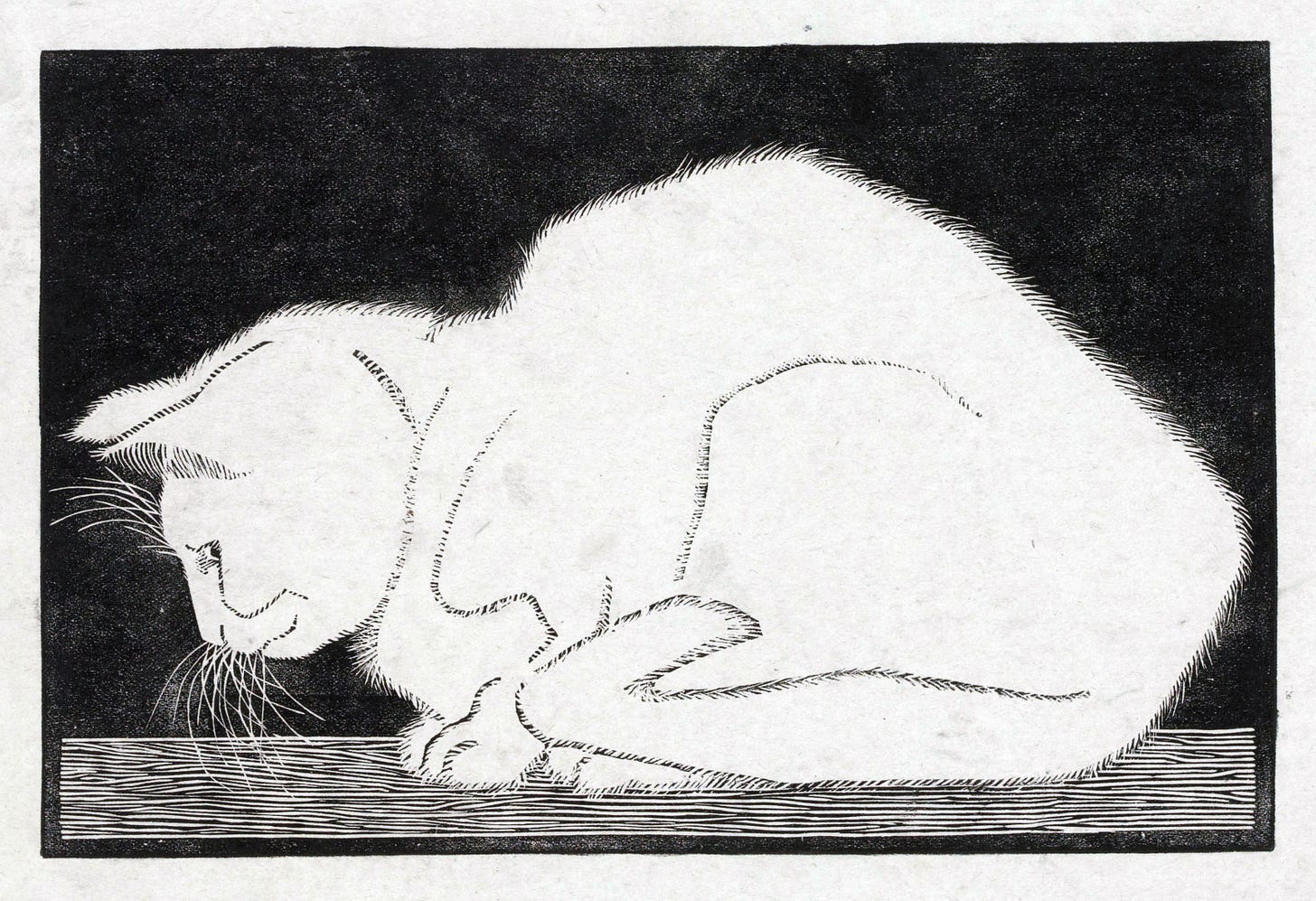

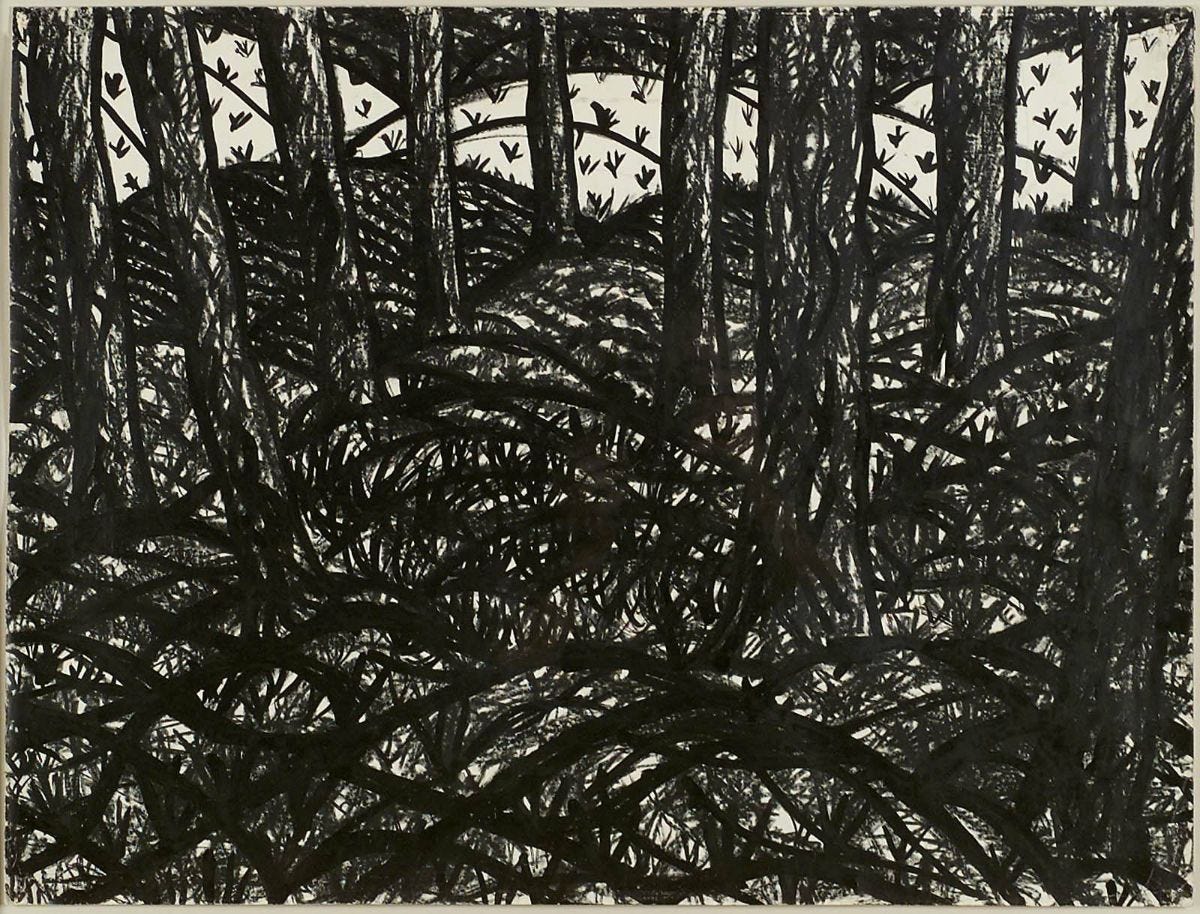

Lamp black, too, is a bit of a trickster. It’s right there in the name—a dark made from light, a blackness from flame. At first, it seems like an opaque color, a true absence of light, blocking color from shining through and forth. But as a paint or an ink, it’s often semi-transparent, allowing you to look though it, down to the bones of the paper or canvas. Many of the house paints on the market labeled “lampblack” are grayish in tone, some even lean towards teal. They’re described as “soft,” “low-luster,” and “timeless.” It is not a warm black; it has no red. When used in a bedroom, I think it has far more character than the glossy, plasticky blacks (which just look tacky, too teen goth). Lamp black asks you to look, rest your eyes, then maybe close them. Sleep.

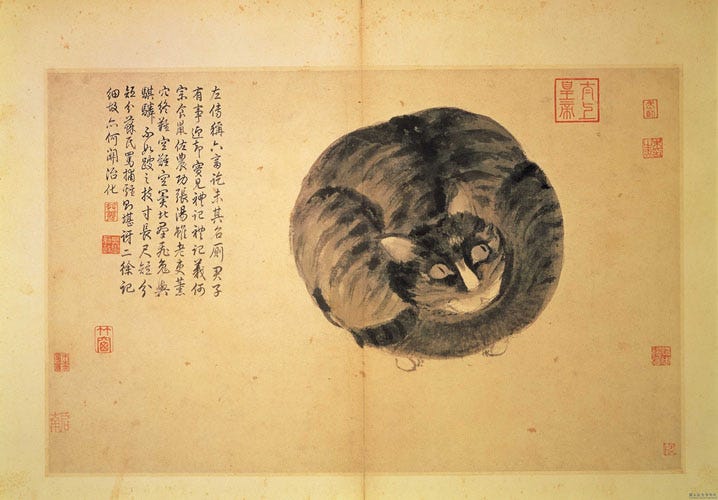

In art history, lampblack is everywhere and nowhere. It’s the ink used in many Chinese brush painting landscapes, it’s the black on the caves of Lascaux, it’s all over papyrus from ancient Egypt, and it’s the dark underlayer for many old masters’ finest works. Lamp black (or carbon black or India ink) is so ordinary that it’s not often listed when talking about paints used by famous artists. It’s just there, in the background, in the shadows. A touch of night added to the lighter colors, a grounding element that allows every other shade to pop.

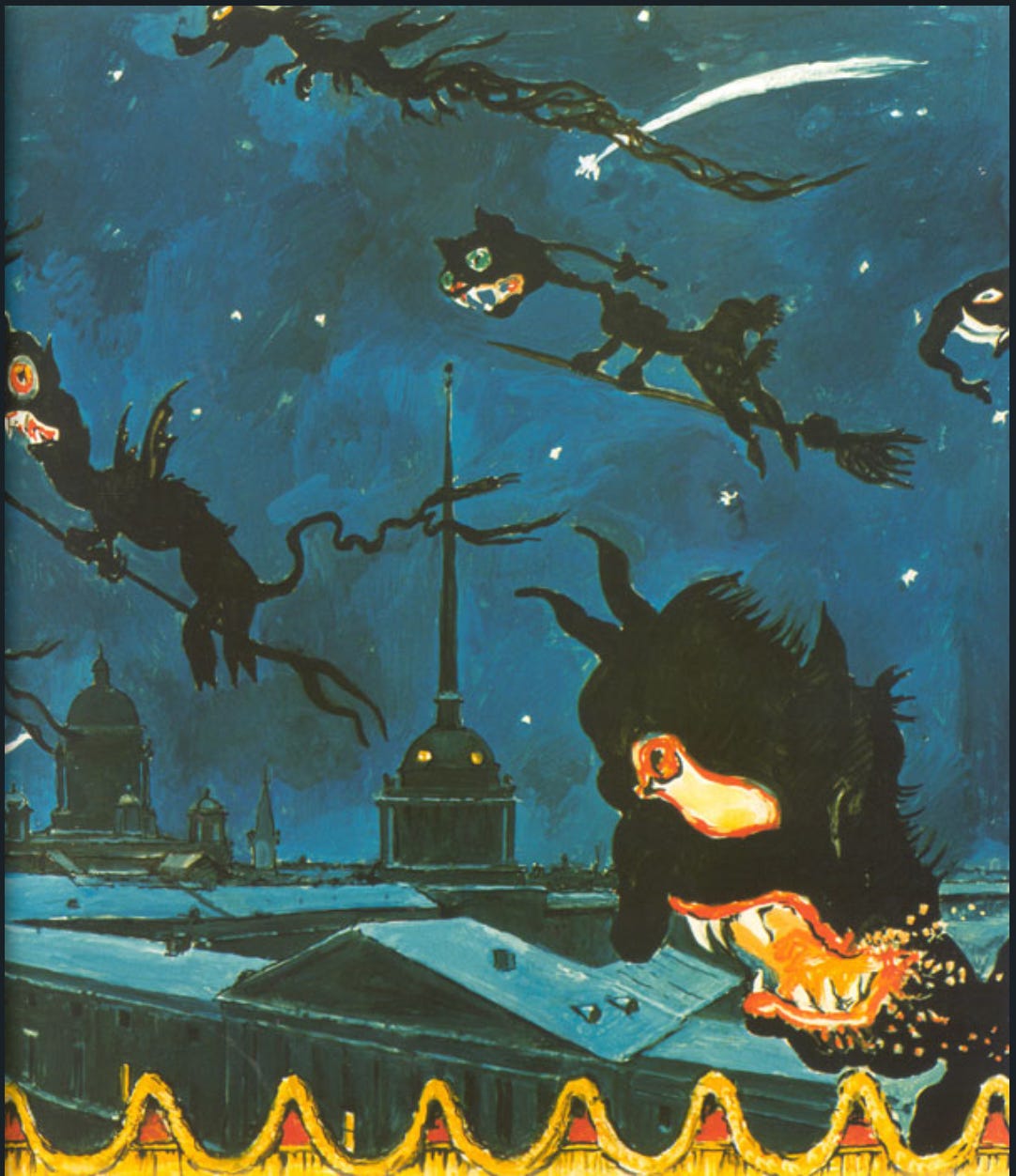

I decided to write about lamp black because we are about to enter the second half of the year. For many northern peoples, there weren’t four seasons (as was the Roman way) or six (as found in ancient south Asian calendars) or seventy-two (the magnificent Japanese micro-season calendar). Instead, there were two: summer and winter. The growing and harvest season lasted from May through October, and the winter and resting season was from November through April. Folklorist Danica Boyce has spoken about this on her excellent podcast, Fair Folk, describing the two halves of the year as a piece of paper folded. October 31 is at the edge of the paper, right where the two halves meet, and this is why it’s such a revered moment in time. There are thin places, and there are thin times. We’re on the cusp of a thin moment, where intangible things briefly, for an evening or an hour, become perceivable. It’s a time of revealing.

You might be wondering what the two-season calendar has to do with lamp black. For me, the importance comes from the significance of soot. There’s a dualism present: the flame, the residue. With every candle, every lamp, there is always both the light and the soot, the bright and the dark, the heat and the cold. (There’s also the smoke, which tends towards gray and perhaps best represents the thin time of autumn, but I’ve written quite enough about gray for now.) For me, winter is a season when I rely on candles to brighten my nights, to replace the glow I miss from my wood stove, albeit in a small, contained way. Candles and their dripping wax, their greasy soot—these always come to dominate my bedside table once the temperature drops.

In some ways, lamp black is the color of revealing, the paradoxical color of unveiling. It can be such a thin color, a worn pigment that disappears with a scratch or a smudge. But it’s also one of the very first colors we ever used to make art—on our hard cave walls, on our fragile soft skin. Carbon blacks, made from the residue of cooking fires, are still in use today. The blackest black in the world, Vantablack, is made of tiny little tubes of carbon. They absorb all the light that shines upon them, creating a super matte dark surface. I’m not trying to say that Vantablack is lamp black—it’s not, it’s a different composition—but that lamp black preceded so many pigments and informed them. It was how we first drew, how we first wrote, how we first made our marks on the world. The thievery of fire was never just about the heat and its possibilities; it was also about the soot and its velvety, quiet qualities, its delicious dark heart.

Love all the research here, as usual, Katy, and the fascinating connections you draw! A great read.

You've got me thinking back to my days in the break room changing the toner cartridge on the ol' copier, getting feathered in velvety, smeary carbon black like an 1890s chimney sweep.

I love this! I was also curious if you’d read Jun'ichirō Tanizaki’s 1933 essay “In Praise of Shadows”. It does not apply itself to art or representation, as such, but it goes into very lyrical depth about the color of darkness in a firelit environment, the shades of blue and purple that swim around in it, etc. You might appreciate it!

Of course it’s worth noting that the actual purpose of the essay is to present an (uncomfortably familiar) ultra-conservative, vulgar and joking-not-joking provocation, with the shadows of candlelight representing “traditional” Japanese culture that’s being lost beneath the lesser shadows of electric lamplight, which represent western influence. BUT if you didn’t know that, you’d assume it’s just an aesthetic appreciation that goes in some bizarre directions.